By Lew Dobbins, Northern California/Lake Tahoe Chapter

Several people have recently asked me questions about winterizing boat engines, so, let’s discuss some of the issues and what we need to do to protect our boat engines and get a long life out of them. Like most things in life, there are a multitude of varying opinions and reasons on what to do to our boats after a season of playing with them. This article is based on my opinion and ex- perience of dealing with marine engines for almost 50 years (damn I’m getting old!). What is written here may or may not be practical (or logical) for your engine or installation. That said, I offer a few options and always welcome your input and comments.

What are we concerned about when laying up our boat engine in the fall? The item we most often think about is the water freezing in the engine, thus rendering it useless after large chunks of cast iron break off due to freezing. This would be “a bad thing” but usually easy to avoid. How about the age old discussion about gasoline and what happens to it after a month or two? Not to mention whether we should fill the tank full or keep it empty? This is a good one. These and several other points are good to think about. Why don’t we look at them one by one and then go through a typical procedure.

What are we concerned about when laying up our boat engine in the fall? The item we most often think about is the water freezing in the engine, thus rendering it useless after large chunks of cast iron break off due to freezing. This would be “a bad thing” but usually easy to avoid. How about the age old discussion about gasoline and what happens to it after a month or two? Not to mention whether we should fill the tank full or keep it empty? This is a good one. These and several other points are good to think about. Why don’t we look at them one by one and then go through a typical procedure.

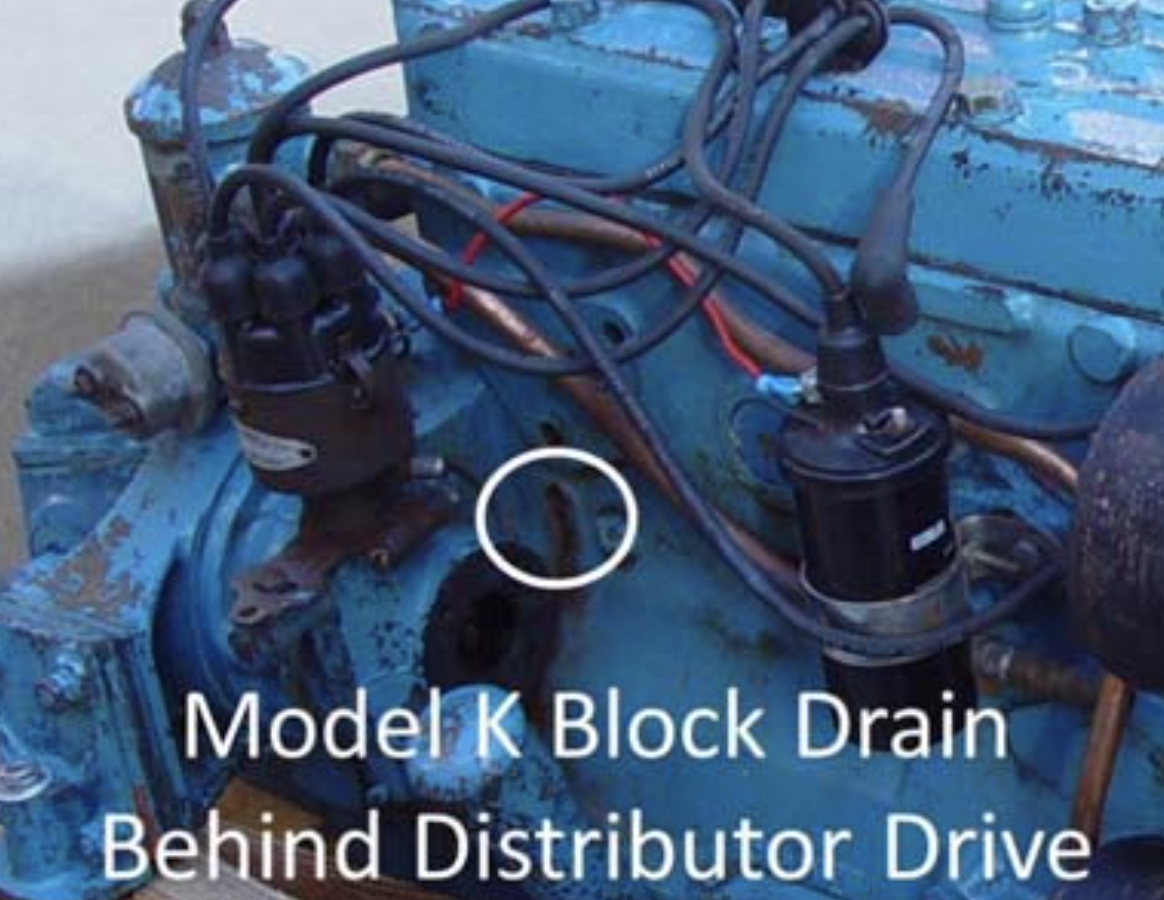

Draining the water from your engine should be a simple thing to do. A Chris Craft (Hercules) flat-head engine will usually have three places to successfully drain the cooling water. These are: 1) Starboard side of the engine block, behind and slightly below the water pump where it couples to

the distributor drive gear housing. 2) The bottom of the water pump casting. 3) The rear or low end of the water jacket of the exhaust manifold in the

case of M and W series engines.

On a K series, the manifold does not have a drain. But it can be drained by either removing the hose feeding the bottom rear of the manifold. The other method is to remove the plug on the bottom of the oil cooler where the water hose exits the cooler to feed the exhaust manifold. These drain points are usually an eighth or quarter inch NPT (National Pipe Thread) port with a drain cock/valve or a brass threaded plug. A drain cock is cer- tainly easy to use but might lie to you. Occasionally they may clog with rust scale or debris from the cooling water. When this happens, you may open the valve and nothing will come out, fool- ing you into thinking it is dry. There are several types of these valves. Some are two pieces that when open- ing, will allow you to com- pletely unscrew the valve leaving a brass open hole to drain or poke and clean. Others look like a small faucet with a 90 degree spout. These are much harder to clean if they get clogged. So why not just use the stock pipe plug? It is easier to get a good flow and to clean a clog. But the down side is that these brass pipe plugs screw into your old and tired cast iron block. When you remove the plug in the fall, the water and air are exposed to the iron threads. This starts the iron oxidation or rust process and the threads deteriorate. After many seasons of this, the threads are gone or destroyed and it becomes very difficult if not impossible to re-install and seal a plug. Leaving a brass valve, sealed with Teflon tape, permanently installed will save your threads.

Other engines and most V-8s are not quite as simple. I am currently working on a Chris Craft small block Chevy V-8 that has 10 drain cocks and 33 hose clamps! While not original to most engines, painting the drain cocks or plugs red will assist in not forgetting any of them. If you have removable drain plugs or two part valves, always place these parts together in some place where you will remember that they need to be re-installed. A small bag tied to the steering wheel with the keys usually works! Normal drain locations for any marine or converted auto engine are: Side of the block, both sides if a V type engine, rear or low end of exhaust manifolds and risers, oil coolers (both transmission and engine if so equipped), water pumps, Many engines will have 2 pumps, a suction pump and a circulation pump. Follow your hoses, they will lead you to the pumps and also show any place that may be a low spot where water may not drain. If you find any of these, then that hose must be removed and drained. This is common on today’s converted auto engines that use the stock circulation water pump. They will have what looks like a radiator hose going into the pump. Draining your engine of all water can have a down side too. Just like with the iron threads of drain holes, the water galleys of the block and heads are now moist with an oxygen rich environment. Just what rust needs to get back to work. A dry environment for storage such as Lake Tahoe or the desert is better for a drained engine than say, Seattle or the San Fran- cisco Bay Area as their average humidity is much higher than the normal low to mid 20s percent of Tahoe.

Other engines and most V-8s are not quite as simple. I am currently working on a Chris Craft small block Chevy V-8 that has 10 drain cocks and 33 hose clamps! While not original to most engines, painting the drain cocks or plugs red will assist in not forgetting any of them. If you have removable drain plugs or two part valves, always place these parts together in some place where you will remember that they need to be re-installed. A small bag tied to the steering wheel with the keys usually works! Normal drain locations for any marine or converted auto engine are: Side of the block, both sides if a V type engine, rear or low end of exhaust manifolds and risers, oil coolers (both transmission and engine if so equipped), water pumps, Many engines will have 2 pumps, a suction pump and a circulation pump. Follow your hoses, they will lead you to the pumps and also show any place that may be a low spot where water may not drain. If you find any of these, then that hose must be removed and drained. This is common on today’s converted auto engines that use the stock circulation water pump. They will have what looks like a radiator hose going into the pump. Draining your engine of all water can have a down side too. Just like with the iron threads of drain holes, the water galleys of the block and heads are now moist with an oxygen rich environment. Just what rust needs to get back to work. A dry environment for storage such as Lake Tahoe or the desert is better for a drained engine than say, Seattle or the San Fran- cisco Bay Area as their average humidity is much higher than the normal low to mid 20s percent of Tahoe.

In some boats, it may be very hard to get to all of the drain locations. Many modern engines often have a knock sensor installed into one side of the block in the drain hole and oil coolers under the floor boards. In these cases, filling the engine with a 50/50 mixture of a bio friendly antifreeze and water will protect your engine. This may also be desirable as a method of deterring internal rust as well. The difficulty of this is that the engine must be at operating temperature and then the mixture needs to be sucked out of a bucket by your suction pump. Enough must be used to ensure that all of the water passages are protected and full. You will know when this happens as antifreeze will start flowing out of your exhaust. Cleanup now and in the spring when you activate the boat is the other down side to this method. So this is not recommended UNLESS you can contain the antifreeze. Engines using rubber or neoprene pump impellers may benefit from this method as it keeps the impeller wet all year. This can aid in staving off hardening of the rubber. The manufacturers rec- ommend that this type of impeller be replaced annually. Remember: Never crank over your engine unless the suction pump has a water supply. A few seconds of dry turning can burn up the impeller. Most all of our pre 1960 engines (with some exceptions) have gear type pumps. These need service too in the form of hav- ing their grease cups filled or cranked up a turn to lubricate the gears and shafts in the pump.

Today’s fuels are not as forgiving as in days past. The storage life of pump gas is about 30 days in a non-sealed container before it starts to

“turn”. All boats, unless newer than January 1, 2009, have a vented tank allowing it to breathe and come in contact with the air. Do not seal your

vent, it needs to be able to breathe for safety and correct operation. Gasoline works so well in our engines as it vaporizes easily aiding even com-

bustion. But that ease of vaporization works against us too. It means that portions of the fuel evaporate easily leaving the heav- ier compounds. Some of the hydro-carbon compounds when in contact with oxygen can combine and create a different compound. The fuel will start to darken and smell more like varnish as it is turning. This process can be slowed down by use of small amounts of any of the off-the-shelf fuel stabilizers. I prefer a product by the name of Sta-Bil from Gold Eagle Co. They have produced a pink in color stabilizer for years and have recently started a new “green marine” Sta-Bil. This new Marine formula deals with water and Ethanol issues better than the original pink formula over prolonged periods of time. Follow the instructions when adding to your fuel tank. Ensure that you run your engine after you add the product. This will assist in protecting your entire fuel system while the boat is in storage. If your boat is only used occasionally through the season, add some with every fillup.

The other question on fuels is regarding storing the boat with an empty tank or a full tank. There are good reasons for and against both. As we mentioned earlier, gasoline evaporates easily and it is actually the fumes or gas vapor when mixed with oxygen that burns and is explosive, not the liquid itself. With this train of thought, a tank that is close to empty is full of explosive vapor. The plus here is that even with an additive, if the boat is stored for long period of time, there is less fuel slowly going bad. Adding fresh fuel then ensures good running. If you leave a tank full with properly treated gas, oxygen (air) is displaced with liquid providing less space for explosive vapor. With the additive, this will slow the process of the gas going bad. But as mentioned, if you are storing the boat for several seasons, you may be draining a lot more fuel only to replace it. Some of our marine fuels (as well as for cars) contain ethanol. This is a form of alcohol and alcohol has a wonderful ability of attracting, mixing with and absorbing water. When a small amount of water is in the fuel system, as often happens with boats, the alcohol combines with the water and will burn. If too much water is attracted by the alcohol, it will separate and sink to the bottom of the tank. Water in our fuel system is not good at any time. Luckily, if the tank is full, with a minimum of oxygen in the fuel tank, we need not worry about rust. The issue of water is where a marine grade fuel filter/water separator is highly recommended to be installed and changed every season. So, empty tank or full tank for storage? You decide what works best for you.

The other question on fuels is regarding storing the boat with an empty tank or a full tank. There are good reasons for and against both. As we mentioned earlier, gasoline evaporates easily and it is actually the fumes or gas vapor when mixed with oxygen that burns and is explosive, not the liquid itself. With this train of thought, a tank that is close to empty is full of explosive vapor. The plus here is that even with an additive, if the boat is stored for long period of time, there is less fuel slowly going bad. Adding fresh fuel then ensures good running. If you leave a tank full with properly treated gas, oxygen (air) is displaced with liquid providing less space for explosive vapor. With the additive, this will slow the process of the gas going bad. But as mentioned, if you are storing the boat for several seasons, you may be draining a lot more fuel only to replace it. Some of our marine fuels (as well as for cars) contain ethanol. This is a form of alcohol and alcohol has a wonderful ability of attracting, mixing with and absorbing water. When a small amount of water is in the fuel system, as often happens with boats, the alcohol combines with the water and will burn. If too much water is attracted by the alcohol, it will separate and sink to the bottom of the tank. Water in our fuel system is not good at any time. Luckily, if the tank is full, with a minimum of oxygen in the fuel tank, we need not worry about rust. The issue of water is where a marine grade fuel filter/water separator is highly recommended to be installed and changed every season. So, empty tank or full tank for storage? You decide what works best for you.

How about the inside of the engine? What do we need to do there? Several things should be addressed and we’ll discuss those next week.

This story originally appeared in the summer 2014 issue of the Northern California Lake Tahoe chapter newsletter.